“I knew they’d use that one,” he says.

Next to the urn, there’s the picture of my mother.

The Picture.

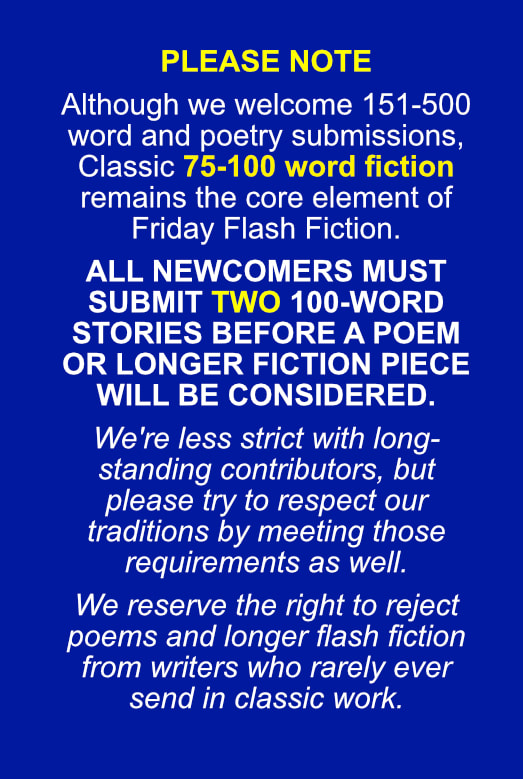

The one that was on the dust sleeves of her books, all one hundred million copies of them.

I’ve seen seen the photo dozens of times, obviously, but for some reason today it seems fresh again.

My dad took it the summer before she published her first book.

Nineteen seventy two.

In it, her hippie vibe has started to wane and she’s looking more like Hip Suburban Mom than Flower Child, her twenties fading into her thirties.but that’s the Mother I remember as a kid.

This is the Mother I remember loving.

This is the Mother who kissed us both on the head in the schoolyard as the bell rang, shooed us off to class, then walked back across the playing fields, through the thin line of trees marking the boundary of our backyard facing the mountains and went inside her cedar shed which my dad built for her as a wedding gift, ostensibly to garden out of.

According to her memoir, she’d write for an hour or so, then go back and do housework.

She referred to cleaning the house daily as her ‘two hours of Victorian servitude,’ a phrase that had apparently resonated with a lot of disgruntled housewives in the Seventies.

She’d finish up her ‘servitude’, have lunch, then come back and write until it was time to pick us up from school.

Like most things that end badly, it started innocently enough.

The year before, my father had seen the ad for the writing class tacked up at the community pool.

She went and everything thing changed.

A couple years before he died, he and I were out somewhere having drinks and he brought that ad up.

“If I’d known,” he’d said, “I’ve have walked right by.”

After that, I’d wonder what we would have all been like if he had.

What it would have been like to have a regular mother.

The thing was, after all this time and all this acclaim of hers, I struggle to remember her being anything other than a writer.

It just grew into this thing that eclipsed everything else before it.

Eclipsed everyone, including my father, who left and eventually found a new life and a new wife back east.

Everyone had assumed she had gotten the house when they split up, until she set the record straight in her book and said that she had bought the house outright from him with the advance from her third book.

She even hired a housekeeper so she could write full-time.

None of this endeared us to our neighbours, who were mostly either housewives themselves or employees of the local logging company who resented the way they were portrayed, albeit fictionally, in my mother’s fourth books, a sort of “Peyton Place” set in the sleepy Pacific Northwest.